The history of Athens

The History of Athens is one of the longest of any city in Europe and in the world. Athens has been continuously inhabited for over 3,000 years, becoming the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BC; its cultural achievements during the 5th century BC laid the foundations of western civilization. Its infrastructure is exemplar to the ancient Greek infrastructure.

During the Middle Ages, the city experienced decline and then recovery under the Byzantine Empire, and was relatively prosperous during the Crusades, benefiting from Italian trade. After a long period of decline under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Athens re-emerged in the 19th century as the capital of the independent Greek state.

Here are a few of the milestones regarding the background of Ancient Athens, throughout recorded history.

Origins and Setting

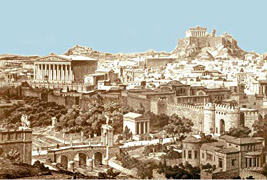

Athens began its history in the Neolithic as a hill-fort on top of the Acropolis ("high city"), some time in the turn between the fouth and the third millennium BC. The Acropolis is a natural defensive position which commands the surrounding plains. The settlement was about 20 km (12 mi) inland from the Saronic Gulf, in the centre of the Cephisian Plain, a fertile dale surrounded by rivers. To the east lies Mount Hymettus, to the north Mount Pentelicus.

As part of Athens in ancient times, the River Cephisus flowed in ancient times through the city. Ancient Athens occupied a very small area compared to the sprawling metropolis of modern Athens. The walled ancient city encompassed an area measuring about 2 km from east to west and slightly less than that from north to south, although at its peak the city had suburbs extending well beyond these walls. The Acropolis was just south of the centre of this walled area. The Agora, the commercial and social centre of the city, was about 400 m (1,312 ft) north of the Acropolis, in what is now the Monastiraki district. The hill of the Pnyx, where the Athenian Assembly met, lay at the western end of the city.

One of the most important religious sites in ancient Athens was the Temple of Athena, known today as the Parthenon, which stood a top the Acropolis, where its evocative ruins still stand. Two other major religious sites, the Temple of Hephaestus (which is still largely intact) and the Temple of Olympian Zeus or Olympeion (once the largest temple in Greece but now in ruins) also lay within the city walls.

Early History

The Acropolis of Athens was inhabited from Neolithic times. By 1400 BC Athens had become a powerful center of the Mycenaean civilization. Unlike other Mycenaean centers, such as Mycenae and Pylos, Athens was not sacked and abandoned at the time of the Doric invasion of about 1200 BC, and the Athenians always maintained that they were "pure" Ionians with no Doric element.

By the 8th century BC Athens had re-emerged, by virtue of its central location in the Greek world, its secure stronghold on the Acropolis and its access to the sea, which gave it a natural advantage over potential rivals such as Thebes and Sparta. From early in the 1st millennium, Athens was a sovereign city-state, ruled at first by kings (see Kings of Athens). The kings stood at the head of a land-owning aristocracy known as the Eupatridae (the "well-born"), whose instrument of government was a Council which met on the Hill of Ares, called the Areopagus. This body appointed the chief city officials, the archons and the polemarch (commander-in-chief).

During this period Athens succeeded in bringing the other towns of Attica under its rule. This process of synoikismos - bringing together in one home - created the largest and wealthiest state on the Greek mainland, but it also created a larger class of people excluded from political life by the nobility. By the 7th century BC social unrest had become widespread, and the Areopagus appointed Draco to draft a strict new lawcode (hence "draconian"). When this failed, they appointed Solon, with a mandate to create a new constitution (594).

Reform and Democracy

The reforms of Solon dealt with both political and economic issues. The economic power of the Eupatridae was reduced by abolishing slavery as a punishment for debt, breaking up large landed estates and freeing up trade and commerce, which allowed the emergence of a prosperous urban trading class. Politically, Solon divided the Athenians into four classes, based on their wealth and their ability to perform military service. The poorest class, the Thetes, who were the majority of the population, received political rights for the first time, being able to vote in the Ecclesia (Assembly), but only the upper classes could hold political office. The Areopagus continued to exist but its powers were reduced.

The new system laid the foundations for what eventually became Athenian democracy, but in the short term it failed to quell class conflict, and after 20 years of unrest the popular party led by Peisistratus, a cousin of Solon, seized power (541). Peisistratus is usually called a tyrant, but the Greek word tyrannos does not mean a cruel and despotic ruler, merely one who took power by force. Peisistratus was in fact a very popular ruler, who made Athens wealthy, powerful, and a centre of culture, and founded the Athenian naval supremacy in the Aegean Sea and beyond. He preserved the Solonian constitution, but made sure that he and his family held all the offices of state.

Peisistratus died in 527, and was succeeded by his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. They proved much less adept rulers, and in 514 Hipparchus was assassinated after a private dispute over a young man (see Harmodius and Aristogeiton). This led Hippias to establish a real dictatorship, which proved very unpopular and was overthrown, with the help of an army from Sparta, in 510. A radical politician of aristocratic background, Cleisthenes, then took charge. He was the one who established democracy in Athens.

The reforms of Cleisthenes replaced the traditional four "tribes" (phyle) with ten new ones, named after legendary heroes and having no class basis: they were in fact electorates. Each tribe was in turn divided into three trittyes while each trittys had one or more demes (see deme) - depending on the population of the demes -, which became the basis of local government. The tribes each elected fifty members to the Boule, a council which governed Athens on a day-to-day basis.

The Assembly was open to all citizens and was both a legislature and a supreme court, except in murder cases and religious matters, which became the only remaining functions of the Areopagus. Most offices were filled by lot, though the ten strategoi (generals) were, for obvious reasons, elected. This system remained remarkably stable, and with a few brief interruptions remained in place for 170 years, until Alexander the Great conquered Athens in 338 BC.

Classical Athens

Prior to the rise of Athens, the city of Sparta considered itself the leader of the Greeks, or hegemon. In 499 BC Athens sent troops to aid the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor, who were rebelling against the Persian Empire (see Ionian Revolt). This provoked two Persian invasions of Greece, both of which were defeated under the leadership of the Athenian soldier-statesmen Miltiades and Themistocles (see Persian Wars).

In 490 the Athenians, lead by Miltiades, defeated the first invasion of the Persians, guided by the king Darius at the Battle of Marathon. In 480 the Persians returned under a new ruler, Xerxes. The Persians had to pass through a narrow strait to get to Athens. A call had been sent via a runner to Sparta for help. The Spartans were in the middle of a religious festival, and so could only send three hundred men. The 300 Spartans and their allies blocked the narrow passageway from the 200,000 men of Xerxes (the Battle of Thermopylae). They held them off for a number of days, but eventually all but one Spartan was killed. This forced the Athenians to evacuate Athens, which was taken by the Persians and seek the protection of their fleet. Subsequently the Athenians and their allies, lead by Themistocles had defeated the still vastly larger Persian navy at sea in the Battle of Salamis. It is interesting to note that Xerxes had built himself a throne on the coast in order to see the Greeks defeated. Instead, the Persians were routed. Sparta's hegemony was passing to Athens, and it was Athens that took the war to Asia Minor. These victories enabled it to bring most of the Aegean and many other parts of Greece together in the Delian League, an Athenian-dominated alliance.

The period from the end of the Persian Wars to the Macedonian conquest marked the zenith of Athens as a center of literature, philosophy and the arts . In this society, the political satire of the Comic poets at the theaters, had a remarkable influence on public opinion. Some of the most important figures of Western cultural and intellectual history lived in Athens during this period: the dramatists Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides and Sophocles, the philosophers Aristotle, Plato and Socrates, the historians Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, the poet Simonides and the sculptor Phidias. The leading statesman of this period was Pericles, who used the tribute paid by the members of the Delian League to build the Parthenon and other great monuments of classical Athens. The city became, in Pericles's words, "the school of Hellas".

Resentment by other cities at the hegemony of Athens led to the Peloponnesian War in 431, which pitted Athens and her increasingly rebellious sea empire against a coalition of land-based states led by Sparta. The conflict marked the end of Athenian command of the sea. The war between the two city-state Sparta had defeated Athens.

The democracy was briefly overthrown by a coup in 411 due to its poor handling of the war, but quickly restored. The war ended with the complete defeat of Athens in 404. Since the defeat was largely blamed on democratic politicians such as Cleon and Cleophon, there was a brief reaction against democracy, aided by the Spartan army (the rule of the Thirty Tyrants). In 403, democracy was restored by Thrasybulus and an amnesty declared.

Sparta's former allies soon turned against her due to her imperialist policy and soon Athens's former enemies Thebes and Corinth had become her allies. Argos, Thebes, Corinth, allied with Athens, fought against Sparta in the indecisive Corinthian War (395 BC - 387 BC). Opposition to Sparta enabled Athens to establish a Second Athenian League. Finally Thebes defeated Sparta in 371 in the Battle of Leuctra. Then the Greek cities (including Athens and Sparta) turned against Thebes whose dominance was stopped at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC) with the death of its military genius leader Epaminondas.

By mid century, however, the northern Greek kingdom of Macedon was becoming dominant in Athenian affairs, despite the warnings of the last great statesman of independent Athens, Demosthenes. In 338 BC the armies of Philip II defeated the other Greek cities at the Battle of Chaeronea, effectively ending Athenian independence. Further, the conquests of his son, Alexander the Great, widened Greek horizons and made the traditional Greek city state obsolete. Athens remained a wealthy city with a brilliant cultural life, but ceased to be an independent power. In the 2nd century, after 200 years of Macedonian supremacy, Greece was absorbed into the Roman Republic.

Roman Athens

In 88-85BC, most Athenian houses and fortifications were leveled by Roman general Sulla, while many civic buildings and monuments were left intact. Under Rome, Athens was given the status of a free city because of its widely admired schools.

The Roman emperor Hadrian would construct, a library, a gymnasium, an aqueduct which is still in use, several temples and sanctuaries, a bridge and would finance the completion of the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

The city was sacked by the Heruli in 267 AD resulting in the burning of all the public buildings, the plundering of the lower city, and the damaging of the Agora and Acropolis. After this the city to the north of the Acropolis was hastily refortified on a smaller scale with the Agora left outside the walls. Athens remained a centre of learning and philosophy during 500 years of Roman rule, patronized by emperors such as Nero and Hadrian.

But the conversion of the Empire to Christianity ended the city's role as a centre of pagan learning; the Emperor Justinian closed the schools of philosophy in 529 AD. This is generally taken to mark the end of the ancient history of Athens.

Byzantine Athens

By 529 AD, Athens was under rule by the Byzantines and had grown out of favor. The Parthenon and Erechtheion were transformed into churches. During the period of the Byzantine Empire Athens was a provincial town, and experienced fluctuating fortunes. In the early years many of its works of art were taken by the emperors to Constantinople.

Furthermore, although the Byzantines retained control of the Aegean and its citys throughout this period, during the seventh and eighth centuries direct control did not extend far beyond the coast. From about 600 the city shrank considerably due to barbarian raids by the Avars and Slavs, and was reduced to a shadow of its former self. As the seventh century progressed, much of Greece was overrun by Slavic peoples from the north, and Athens entered a period of uncertainty and insecurity. The one notable figure from this period is the Empress Irene of Athens, a native Athenian, who seized control of the Byzantine Empire in a palace coup.

By the middle of the 9th century, as Greece was fully reconquered again, the city began to recover. Just as other cities benefited from improved security and the restoration of effective central control during this period, so Athens expanded once more.

The invasions of the Turks after the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the ensuing civil wars largely passed the region by, and Athens continued its provincial existence unharmed. When the Byzantine Empire was rescued by the resolute leadership of the three Komnenos emperors Alexios, John and Manuel, Attica and the rest of Greece prospered.

Archaeological evidence tells us that the medieval town experienced a period of rapid and sustained growth, starting in the eleventh century and continuing until the end of the twelfth century. The agora or marketplace, which had been deserted since late antiquity, began to be built over, and soon the town became an important centre for the production of soaps and dyes. The growth of the town attracted the Venetians, and various other traders who frequented the ports of the Aegean, to Athens. This interest in trade appears to have further increased the economic prosperity of the town.

The 11th and 12th centuries were the Golden Age of Byzantine art in Athens. Almost all of the most important Byzantine churches around Athens were built during these two centuries, and this reflects the growth of the town in general. However, this medieval prosperity was not to last. In 1204, the Fourth Crusade conquered Athens and the city was not recovered from the Latins before it was taken by the Ottoman Turks. It did not become Greek in government again until the 19th century.

Latin Athens

From 1204 until 1458, Athens was ruled by Latins in three separate periods. It was initially the capital of the eponymous Duchy of Athens, a fief of the Latin Empire which replaced Byzantium. After Thebes became a possession of the Latin dukes, which were of the Burgundian family called De la Roche, it replaced Athens as the capital and seat of government, though Athens remained the most influential ecclesiastical centre in the duchy and site of a prime fortress. In 1311, Athens was conquered by the Catalan Company, a band of mercenaries called almogávares. It was held by the Catalans until 1388. After 1379, when Thebes was lost, it became the capital of the duchy again. In 1388, the Florentine Nerio I Acciajuoli took the city and made himself duke. His descendants ruled the city (as their capital) until the Turkish conquest of 1458. It was the last Latin state in Greece to fall.

Burgundian period

Under the Burgundian dukes, a bell tower was added to the Parthenon. The Burgundians brought chivalry and tournaments to Athens; they also fortified the Acropolis. They were themselves influenced by Greek culture and their court was a syncretistic mix of classical knowledge and French knightly haute couture.

Catalan period

The history of Catalan Athens, called Cetines (rarely Athenes) by the conquerors, is most obscure. Athens was a veguería with its own castellan, captain, and veguer. At some point during the Catalan period, the Acropolis was further fortified and the Athenian archdiocese received an extra two suffragan sees.

Florentine period

The Florentines had to dispute the city with the Republic of Venice, but they ultimately emerged victorious after seven years of Venetian rule (1395-1402).

Othman Athens

Finally, in 1458, Athens fell to the Ottoman Empire. As the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror rode into the city, he was greatly struck by the beauty of its ancient monuments and issued a firman (imperial edict) forbidding their looting or destruction, on pain of death. The Parthenon was converted into Athen's main mosque.

Despite the initial efforts of the Ottoman authorities to turn Athens into a model provincial capital, the city's population severely declined and by the 17th century it was a mere village. Great damage to Athens was caused in the 17th century, when Ottoman power was declining. The Turks would begin a practice of storing gun powder and explosives in the Parthenon and Propylaea. In 1640, a lighting bolt would strike the Propylaea, causing its destruction.

In 1687, Athens was besieged by the Venetians, and the temple of Athena Nike was dismantled by the Ottomans to fortify the Parthenon. A shot fired during the bombardment of the Acropolis caused a powder magazine in the Parthenon to explode, and the building was severely damaged, giving it the appearance we see today. The occupation of the Acropolis continued for six months, but even the Venetians participated in the looting of the Parthenon. One of the west pediments of the Parthenon would be removed causing even more damage to the structure. The following year Turkish forces set fire to the city. Ancient monuments were destroyed to provide material for a new wall with which the Ottomans surrounded the city in 1778.

Between 1801 and 1805 Lord Elgin, the British resident at Athens, removed reliefs from the Parthenon (see Elgin marbles for more detail.) Along with the Panatheniac frieze, one of the six caryatids of the Erechtheion was extracted and replaced with a plaster mold. All in all, fifty sculptural pieces were carried away from the Parthenon including three fragments purchased by the French.

In 1822 a Greek insurgency captured the city, but it fell to the Ottomans again in 1826. Again the ancient monuments suffered badly. Partially funded by Lord Byron, the Greeks continued to fight. Ottoman forces remained in possession until 1833, when they withdrew and Athens was chosen as the capital of the newly established kingdom of Greece. At that time the city was virtually uninhabited, being merely a cluster of buildings at the foot of the Acropolis, where the Plaka district is now.

Modern Athens

In 1832, Otto, Prince of Bavaria was proclaimed King of Greece. He adopted the Greek spelling of his name, King Othon as well as Greek national dress, and moved the capital of Greece back to Athens. Othon's first task as king was to make a detailed archaeological and topographical survey of Athens. He assigned Gustav Eduard Schaubert and Stamatios Kleanthes to complete this task. At that time Athens had a population of roughly 4,000-5,000 people, located in what today covers the district of Plaka in Athens.

Athens was chosen as the Greek capital for historical and sentimental reasons, not because it was a large city: there are few buildings in Athens from the period of Byzantine Empire and the 18th century. Once the capital was established there, a modern city plan was laid out and public buildings erected.

The finest legacy of this period are the buildings of the University of Athens (1837), Old Royal Palace (now the Greek Parliament Building) (1843), the National Garden of Athens (1840), the National Library of Greece (1842), the Greek National Academy (1885), the Zappeion Exhibition Hall (1878), the Old Parliament Building (1858), the New Royal Palace (now the Presidential Palace) (1897) and the Athens Town Hall (1874).

Athens experienced its first period of explosive growth following the disastrous war with Turkey in 1921, when more than a million Greek refugees from Asia Minor were resettled in Greece. Suburbs such as Nea Ionia and Nea Smyrni began as refugee settlements on the Athens outskirts.

Athens was occupied by the Germans during World War II and experienced terrible privations during the later years of the war. In 1944 there was heavy fighting in the city between Communist forces and the royalists backed by the British.

After World War II the city began to grow again as people migrated from the villages and islands to find work. Greek entry into the European Union in 1981 brought a flood of new investment to the city, but also increasing social and environmental problems. Athens had some of the worst traffic congestion and air pollution in the world. This posed a new threat to the ancient monuments of Athens, as traffic vibration weakened foundations and air pollution corroded marble. The city's environmental and infrastructure problems were the main reason Athens failed to secure the 1996 centenary Olympic Games.

After this, both the city of Athens and the Greek government, aided by European Union funds, undertook major infrastructure projects such as the new Athens Airport and a new metro system. The city also tackled air pollution by restricting the use of cars in the centre of the city. As a result, Athens was awarded the 2004 Olympic Games. Despite the scepticism of many observers, the games were a great success and brought renewed international prestige (and tourism revenue) to Athens.